|

Precious metals prices have been on a tear for a while and as a result, plenty of places seem to be buying and selling. Even Costco is offering gold bars online and according to no less than the Wall Street Journal, they are flying off their digital shelves. Whether or not to buy physical gold is up to you but if you are thinking about selling some gold (or silver), here are some things to consider in order to get the best price possible.

Knowledge is power and before you approach a gold buyer, I strongly suggest you do your homework and get a good handle on what your gold is worth beforehand. This isn't hard to do and the steps you need to do are presented below. What you will need to know is 1) what kind of gold you have, 2) how much it weighs, and 3) what the spot price is on the day you are going to sell. Once you have that in hand, you are ready to do some simple math and learn your gold or silver's value. In my previous blog post, I covered the marks you need to find to determine the purity of your gold, which will have a large bearing on how much you are going to get for it. Here, though, is a quick recap: Most gold is done in levels, these being 22K, 18K, 14K, and 10K. Typically, gold will either be marked in this way or with a number that represents a percentage of 24K, which is pure gold. 18K gold may be marked, for example .750, which is 75% of 24. Often times gold marks are tiny and hard to find so I recommend having a good magnifying glass on hand and also being patient. Marks that indicate a piece is not gold include "rolled gold", GF (gold filled), and "gold plated". Silver will typically be marked "Sterling", .925, .800, or "coin". If you see "EPNS" or "EP", that means silver plate and thus little to no value. One note: British silver is often marked only with hallmarks. The key mark will be a striding lion with one paw in the air, which is the hallmark for sterling silver. Once you know your item's purity, it is time to weigh it. Gold and silver are measured in troy ounces, which complicates things since a troy ounce weighs more than a standard ounce. The easiest thing to do is just skip all that and weigh your gold and silver in grams. You can get small jewelry scales on Amazon for very little money but you can also use a digital postal scale. Just make sure you have the scale set to "grams" before weighing it. The next step is to find out the current price of gold/silver. Gold and silver prices fluctuate constantly and are keyed to what is called the "spot price". This is something that you can quickly find by simply googling "gold spot price in grams today" and instantly you will see a variety of metals-related websites that will display the current price in grams up to the minute. You can even specify "14K gold spot price in grams" if you want to skip some math. For silver, you will just be looking for the sterling spot price in grams. At this point you are ready to do your value calculation. You simply will multiply the number of grams you have times the spot price and that is your full value, also called the melt value. Now, will you get that? No, you will not... the metals buyer needs to make a profit so you will be receiving a percentage of the melt value. That percentage will vary between buyers and be sure to ask the question right up front: "What percentage of melt value do you pay?" If you are not getting at least 80% of melt value, then my advice is to head elsewhere. Currently, the fellow to whom I sell estate gold and silver pays 92% of melt for gold and 85% for silver, which should give you a decent point of reference. Also, when you do elect to do business with a metals buyer, insist they weigh the items in grams like you did. Don't let them wave around troy ounces, pennyweights, or any other unit of weight... get it in grams so there is no room for misunderstanding. Here is a sample calculation: You find that the spot price of 14K gold is $44.50. You have 12 grams of 14K gold. $44.50 x 12 = $533.33, which is your full melt value. Buyer is offering 85% of melt value, so you get: $533.33 x 0.85 = $453.33 By doing this math ahead of time, you can walk into any buyer's store and know immediately if something is off if their calculation is dramatically different from your own. Note: if your gold item is a piece of jewelry and there are semiprecious stones, understand that these stones will have no value and will likely be discounted from the total weight of the piece by the metals buyer. Lastly, do the obvious homework and google whomever you are thinking of doing business with before walking in their door. If they are dealing less than fairly, it will likely show up in their reviews and thus will save you a trip (and, potentially, a lot of money). Happy selling! Bryan Roberts

0 Comments

With gold prices being as high as they are, now is a good time to for a quick refresher on precious metals marks. Even small amounts of scrap gold can quickly add up, so you may have some ready cash lying around and not even realize it.

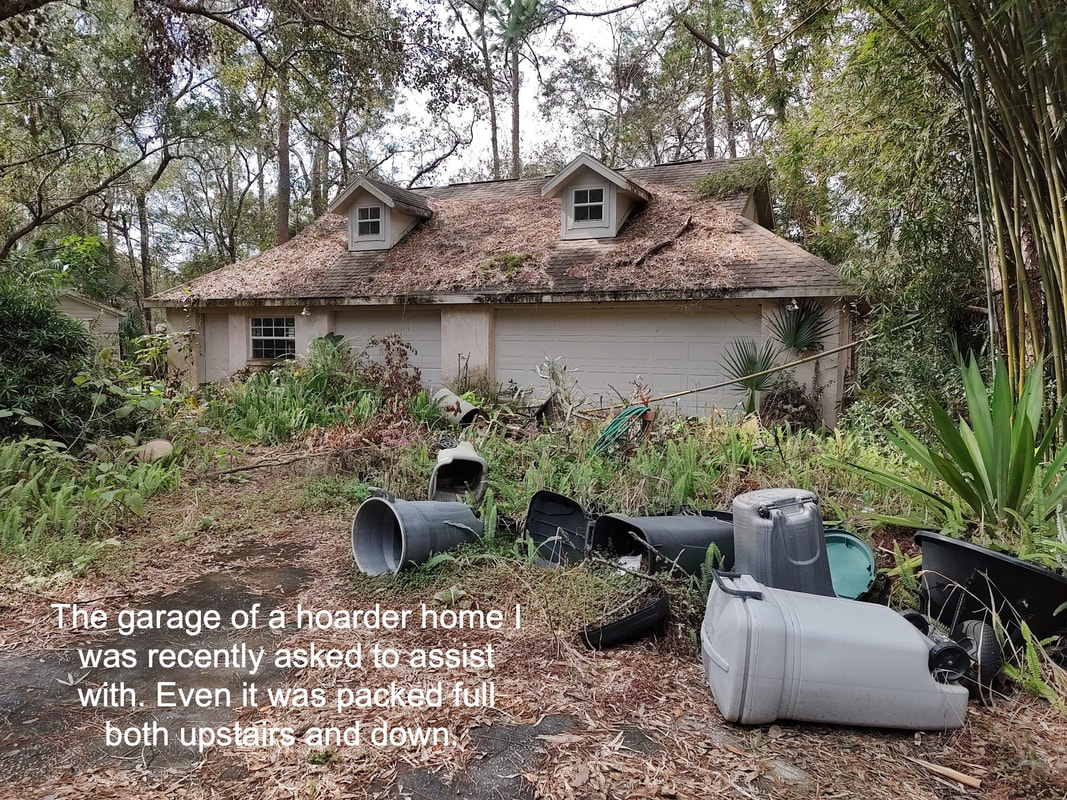

Pure gold is 24K but typically isn't used for jewelry due to its softness. Instead, gold is mixed with base metals such as copper for, which adds hardness but also lowers the purity. Most gold is done in levels, these being 22K, 18K, 14K, and 10K. Typically, gold will either be marked in this way or with a number that represents a percentage of 24K. 18K gold may be marked, for example .750, with is 75% of 24. Often times gold marks are tiny and hard to find, as shown in the above photo. Also remember that gold can be white, so don't assume your ring, etc, is sterling silver. Marks that indicate a piece is not gold include "rolled gold", GF (gold filled), and "gold plated". Speaking of silver, it remains gold's poor cousin and won't have much value unless you have a lot of it. So, think sets of sterling flatware, hollowware pieces such as vases, etc. Silver will typically be marked "Sterling", .925, .800, or "coin". If you see "EPNS" or "EP", that means silver plate and thus little to no value. One note: British silver is often marked only with hallmarks. The key mark will be a striding lion with one paw in the air, which is the hallmark for sterling silver. Your best friend in all this will be a good magnifying glass, especially a loupe. Again, the marks can be very hard to find but the payoff can be considerable. So, with gold quite high, now is a good time to take a peek in the jewelry box to see if there is anything you might want to bring to market. Hoarder homes present a challenge both to an appraiser such as myself and those who are dealing with the person suffering from the disorder. Here are a few tips if you are confronted with a hoarding situation.

First, remember that a true hoarder typically has a distorted concept of value. In other words, a diamond ring and a Kmart plastic bracelet hold the same importance and will be treated as such. So, trying to "help" them by removing what appears to be clutter and rubbish can be quite traumatic for the hoarder. Second, when it comes time to clear a hoarder home, remember that money and valuables can (and usually will) be stashed in a wide variety of places. This means every garment pocket, every shoe, and every purse needs to be searched, as well as books flipped through for dollar bills. Likewise, a detailed search of all drawers will likely be needed as well. Hoarders can be very creative when looking to hide things. Third, when considering whether to intervene with a relative or friend, start early. Guardianships and POA's can be a lengthy process and will typically require the involvement of both legal and medical professionals. From my own professional experience, there is often a dementia component to the hoarding as well, which can thus place the hoarder at risk of injury within their home (degraded environmental conditions, etc.) Lastly, be compassionate. Serious hoarding is a distinct recognized mental disorder and as frustrating as the situation can be, the hoarders are still just people with mental challenges, not kooks as they are often made out to be on TV. Again, involve the proper medical and legal authorities as needed to make things go as smoothly as possible. An interesting phenomenon of the 19th century was the popularity of "love tokens". Although they had been around long before, the love token became an enormous fad both in England and America in the second half of the 19th century. At their most basic, they were a small item, typically a smoothed coin, mounted on a stick pin or hat pin and engraved with initials, meaningful designs, etc. Many, if not most, love tokens were simply made affairs... often done by roadside craftsmen who would produce desired pieces in short order.

Love tokens were used for a variety of purposes... many would have the initials of a loved one and often times would serve as a de facto engagement ring for those that could not afford one. Others would be given to departing spouses or other family members headed to sea, military deployments, etc. Still others served as mourning jewelry items. The latter purpose was tied directly to the Victorian fascination with mourning, encouraged in large measure by Queen Victoria's decades-long mourning for Prince Albert. The popularity of love tokens arguably reached its zenith in the period 1860-1890. In America, they became so popular during those decades that it caused a noticeable shortage of dimes for a period of time (dimes were evidently the most popular coins to make into a love token). Their popularity waned with the end of the Victorian era, however, and today they are largely a historic curiosity. There is a popular collector base for them, however, and today you can expect to pay between $25 and $100 for the average love token. Bohemian glass, also referred to as Bohemia glass, is a broad term applied to the fine crystal made primarily in the Czech Republic and surrounding areas. The tradition of fine cut and decorated glass in the region goes back to the Renaissance and archeological excavations have even found evidence of glass making as far back as 1250.

The type of Bohemian glass most people are familiar with are the colorful hock glasses that feature colored glass cut to clear in ornate patterns. These remain popular to this day and makers such as Ajka produce some of the finest examples. Other items to be found are vases, decanter sets, barware of various sorts, and elegant bowls and plates. Not surprisingly, there are nuances to know before making a purchase of a vintage piece. As with any glass, condition is paramount since even a small chip will clobber a piece's value. Also, certain colors such as cobalt and ruby are more desirable than others such as amber. Makers are important as well... expect to pay a premium for pieces by makers such as Ajka and Val Saint Lambert versus lesser known makers. Even within a given maker, certain patterns and forms will command a higher price. A good example is the set of champagne flutes pictured above, which are in Ajka's most desirable pattern called Marsala. And within that pattern, the champagne flutes are the forms that command the highest price among the stemware. So, if you are looking to buy for resale, a basic working knowledge of these nuances can pay big dividends. One other tip: avoid decanters missing their stoppers and those with stoppers that are mis-matched. Lastly, beware of reproductions. On occasion you will find new pressed glass made to look like true Bohemian crystal. The tipoffs there will be mold seams, no "ring" to the glass when flicked on the rim by a fingernail, and generally lesser glass quality. True Bohemian glass is lead crystal, both hand made and hand cut. Like most everything else, the prices for Bohemian glass have come down considerably in the past few decades. The good news is that this means truly wonderful pieces of crystal can be had for surprisingly modest sums. Put the above tips into practice, do a little homework, and then start prowling your area resale and thrift stores... you may be amazed at the deals you can bring home. Authentication of high-end artwork is a complex process and since it does come up from time to time in my appraisal duties, it is worth exploring here. What many people are not aware is that most prominent painters (think Picasso, Rembrandt, and others) have a recognized expert or committee of experts upon which auction houses and collectors typically rely. While an appraiser can value a work on the assumption that the piece is genuine, for an auction house to be willing to sell a work by a prominent artist, they will likely insist on first having the work validated at the consignor's expense. Sometimes this can be avoided if the painting appears in a recognized catalog of the artist's work (called a catalog raisonné). Otherwise, the auction house will send high-resolution images of the work to the recognized expert (s) and abide by their verdict.

A downside to this, of course, is that if the work is indeed genuine but the expert says otherwise, the work will be considered by the art market to not be authentic. And if that is the case, the work will be largely unsellable as a genuine work by the artist. This has led to some serious legal dustups in past years... enough so that the committees for some artists such as Warhol and Rothko have actually disbanded due to the cost and threat of litigation. In one instance, an expert who was preparing a catalog raisonné for a prominent painter abandoned the project after actually receiving death threats from owners concerned their works would be deemed fake. So, if you have a work by a major artist and you are considering the idea of bringing it to market, be aware that the process may be complex and also involve having to invest some money up front. With precious metals prices at strong levels, it is more important than ever to make sure you don't miss gold or silver when bringing estate items to market. Most everyone knows to look for the all-important "sterling" mark on a piece of flatware or hollowware but coin silver an easily get overlooked.

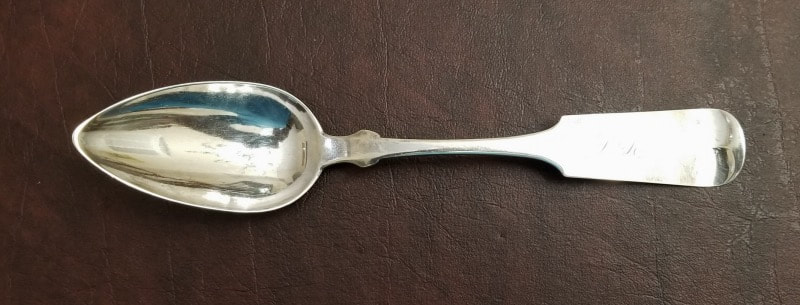

What is coin silver? It is the grade of silver used by American silversmiths prior to the establishment of the assay system in the late 19th century. The term is derived from the fact that the silver content was the same as that used for coins of the day. Typically, coin silver is almost identical to sterling silver in purity and sometimes exceeds it. Marking was sporadic... typically, the maker's name would be stamped and occasionally the phrase,"pure coin". In many cases, there is only a single symbol which makes identification of the maker challenging. Still other pieces bear "pseudo hallmarks", which were meaningless symbols made to imitate the marks of British silver, which was considered superior at the time. One tipoff that an item might be coin silver will be the form. On flatware, especially spoons and ladles, the handles typically are simple affairs in a fiddle shape. On especially early pieces, you might also see that the bowl and handle were two separate pieces that were joined together. Yet another tipoff is the absence of any mark such as EPNS denoting silver plate. Lastly, coin items when polished will look like sterling plus will often be fairly light since there is no base metal, as in plated items. Like most sterling pieces, coin silver items are typically going to be worth their melt value more than anything else. The exception will be when the piece is by a prominent silversmith or is a fine example of silversmithing, such as an ornate teapot or ladle. There are several reference books available to identify early American silversmiths as well as one or two free online databases. These are always worth checking since some makers can bring considerable sums. Paul Revere, of course, is perhaps the most famous but certain southern makers, especially from Charleston and New Orleans, can bring handsome sums as well. Many of us have seen Tiffany lamps with distinctive glowing gold glass shades. The term for this type of glass is "aurene" and it became popular among high-end glass companies beginning in the early 20th century. Interestingly, it was Steuben Glass that first created aurene glass c. 1910 and today they remain the company most associated with it.

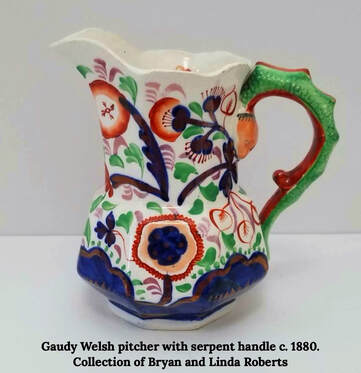

The term "aurene" was derived by combining the first three letters of the Latin word for gold (aurum) with the Middle English spelling of sheen (schene). The process of creating aurene glass was both complex and ingenious. When being fired, the glass was sprayed with stannous chloride, which coated the surface with microscopic ridges. The ridges reflected and refracted light striking the glass and in turn produced the lovely soft golden (or silver) glow of aurene. Depending on the salts used in the making of the glass, aurene could be gold, silver, or a bluish color. While Steuben pioneered aurene glass, other companies quickly adopted the process to their own lines, including Tiffany, Loetz, and Quezal. Today it remains popular with collectors and always brings a premium versus other, more common glass. One of the most colorful products of the 19th century was pottery known as "Gaudy Welsh". Produced mainly in the Staffordshire district by companies such as Allerton Brothers, Gaudy Welsh in some ways represented a transition form hand-made pottery to mass-produced wares. It was produced in large quantities and was intended as everyday ware for the working class. Unlike the carefully crafted slipware with elegant, intricate designs, Gaudy Welsh had loose, colorful polychrome decoration highlighted with lustre that in some ways was akin to folk art and in other ways almost modernist.

The motto was, "cheap and cheerful" and that certainly summed up Gaudy Welsh. Like carnival glass, Gaudy Welsh was sold for very small sums and could often be purchased at fairs and markets. It came in all the usual forms, but most often one sees hollowware such as small pitchers and cups and saucers. Most pieces were utilitarian in design but some pieces have elegant forms and in some instances, unusual polychrome handles. The Allerton serpent-handled pitcher in the above photo is a good example. The principle years of Gaudy Welsh production were 1840-1900. Despite the bold color and antique status, pieces of Gaudy Welsh can be had for remarkably small sums on sites such as Etsy and eBay. They make wonderful splashes of color and visual interest and the loose decoration means that a piece of Gaudy Welsh won't look out of place in a contemporary setting. One of the more interesting things to be produced throughout the 19th century were "laydown" or "throwaway" perfume bottles. Made mostly in Czechoslovakia, Turkey, and England, these were hand-pulled bottles about 6 or 7 inches long that carried a small amount of perfume in them. They were essentially free samples and the bottles were made to be discarded. Nontheless, they were usually beautifully decorated, typically with gilt paint and enameling. Most were crystal and square-sided; less common (and more desireable) are those of spiral form and of colored glass.

Now... about that "tearful revelation". Mourning became a serious affair in England with the death of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria's difficulty in getting past it. Mourning jewelry, photography, and other related areas all became part of everyday society. One notion that has been revealed to be a myth, however, is that the laydown perfume bottles were for collecting tears while mourning a loss. This myth became so pervasive, in fact, that another name for these bottles is a "tear catcher" or a "lachrymatory". While it makes for an interesting story, it should also be regarded as the antiques equivalent of an urban myth. Lastly, if you are fortunate enough to run across one or more of these bottles, expect to pay retail price between $100 to $300 apiece. |

AuthorBryan H. Roberts is a professional appraiser in Sarasota, FL. He is a member of the Florida State Guardianship Association and currently serves on the board of the local FSGA chapter. He is a past president of the Sarasota County Aging Network, a non-profit that provides grants to other non-profits benefiting seniors in need and is also a board member of PEL, an area non-profit whose resale store profits support programs and scholarships for at-risk and disadvantaged youth. He is certified in the latest Uniform Standards of Appraisal Practice (USPAP) Equivalent Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed