|

Native American jewelry remains a popular collecting category these days. It is a broad subject but here is a an overview to get you started.

Most pieces of NatAm jewelry are crafted of sterling silver and set with semi-precious stones associated with the American southwest. Turquoise is especially common in such pieces but you will also see jasper, onyx, coral, and many others as well. Within turquoise there are many different types, ranging to the pure greenish blue to "matrix turquoise", which is polished matrix with embedded streaks and pockets of turquoise. Finely crushed turquoise is also commonly seen. The Zuni and Navajo peoples arguably have the deepest tradition of jewelry making but Hopi and other tribes crafted wonderful pieces as well (and continue to do so today). Identification can sometimes be a challenge, however. Many NatAm silversmiths used only their initials or, in some cases, a single symbol such as rising sun mark. Information is rather fragmentary on the internet and often times you will have the most success in ID'ing your pieces by turning to physical reference books. Also, be aware that often times a piece may not be marked "sterling" even though it is (Native American makers are, I believe, exempt from US Federal assay marking requirements). Because many people brought back pieces from western trips and vacations, nice examples of NatAm jewelry can turn up almost anywhere. Personally, I have made some of my best finds going through the cases of flea market dealers and resale stores since often times, they haven't taken the time to research a piece and identify a prominent maker. The Jackie Singer bracelet shown above, for example, is only marked "J S". Singer was a prominent Navajo maker and the piece is 60 grams of sterling silver, even though it is not marked as sterling. Value will naturally be guided by several factors. These include the maker, the level of craftsmanship, the amount of silver used, condition, and age. In general, older is better and a prominent maker will always be more desirable than a lesser-known silversmith. Sadly, fakes abound so be alert for "too good to be true" deals. In the meantime, happy hunting! If you spend any time around older paintings, you will inevitably bump up against the subject of restoration. By now, most of us have seen the various articles on one or two botched restoration efforts of Old Master works in Spain, with the best-known one being the 2012 incident at a church near Zaragoza. This attempt at restoration, done by a well-meaning elderly parishioner, was so dreadful that the result became known as the "monkey Christ". And yes, it was that bad.

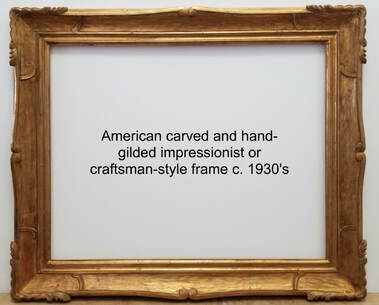

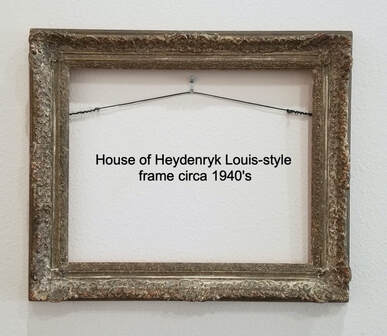

Fortunately, most of us aren't going to be tasked with repairing 16th century works of art anytime soon. But, you may come face to face with the topic of restoration if you are thinking of buying, and perhaps even re-selling, an historic work. The first thing to know is that a little well-done restoration is not a deal-breaker... in fact, many famous paintings in museums have significant amounts of restoration. The rule of thumb when buying a painting is 10%... if more than that amount of the painting has been repaired, then you need to factor it into the price of the work. Clues as to it having been repaired will be visible patches on the back, areas on the front where the textures and finish are different (often times repaired areas are very smooth) and perhaps poor color matches in the repaired areas. Another clue will be if the painting has been lined. Often called "re-lined", which is actually incorrect (that would imply the painting has been lined twice), lining is where the canvas has been infused with wax to stabilize loose and cracked paint, torn areas, etc. Lining is a perfectly standard restoration technique but it often means the painting had fairly serious condition issues. Overpainting, also called in-painting, can usually be detected by the use of a UV light. Unfortunately, sophisticated masking varnishes are available now and clever sellers will sometimes employ these to hide the extent of the overpainting. Masking varnishes tend to glow green under a UV light so if you see that it has been used, tread carefully... there is no need for a masking varnish unless someone is trying to hide something. Having a painting cleaned is also a standard restoration practice and usually adds value to the work unless poorly done. Certain paints such as many greens are chemically unstable and are referred to as "fugitive colors". Thus, someone who gets careless in cleaning a painting can easily take these colors off, in which case the painting is referred to as having been "skinned". Suffice to say, this really clobbers the value of a painting. If you are unsure if a painting is dirty, look at the edges nearest the frame. Often times you will see a thin line of true color and this can give you a sense of what potential the painting might have. Back in my dealer days, I did vey well by buying dirty but good quality paintings since most people didn't realize how good the piece would be when cleaned. As far as the dirt goes, a gray cast often means the painting was in a home with fuel oil or coal heat. An orange cast (and sometimes accompanying odor) means nicotine. Fortunately, both usually come off rather easily with some simple household cleaners. I won't go into details here but anyone who is interested in a DIY approach is welcome to contact me for some instructions. You will want to do that before blasting away, though, trust me. One 'monkey Christ" is enough ;-) As with most categories, the market for period frames is well off its high, which was reached in the early 2000's. That said, good frames can still bring money. Here are some things to look for if you are on the hunt.

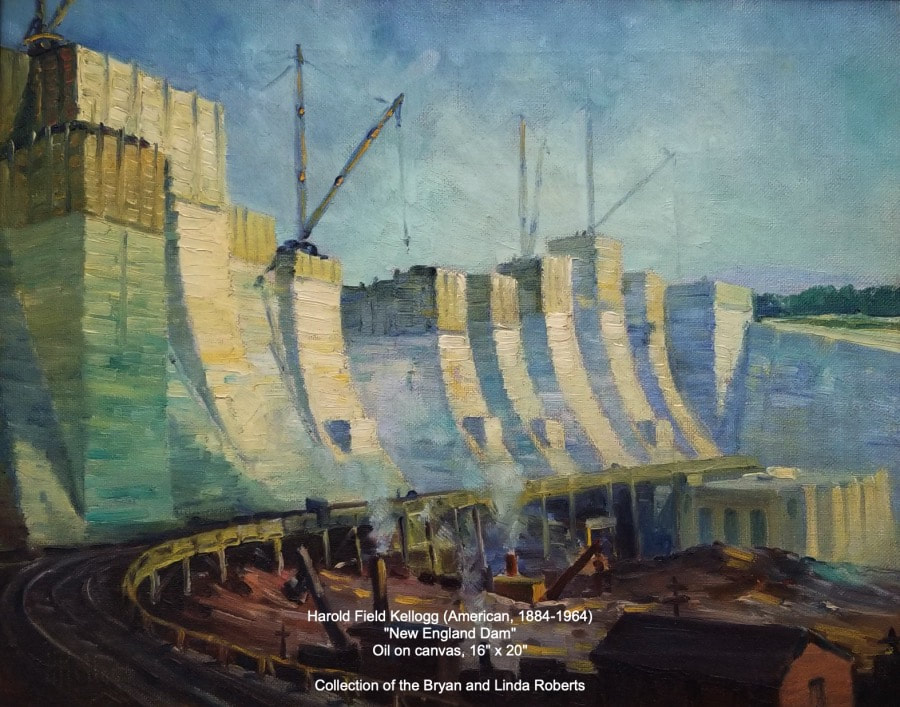

First, a little history. The earliest frames were actually carved wood with gilding applied to them. Or, in the case of the Dutch, often it was a black finish. These early carved frames are valuable but also highly uncommon, so the odds fo finding one from the 16th or 17th century are pretty low, at least here in the US. For American frames, the highest dollar value frames typically will be those made by either a master frame maker like Stanford White or one of the master impressionists like Childe Hassam. These frames can bring north of $10,000 at auction. Suffice to say, they are pretty rare and not something you will likely find in a general re-sale or antiques store. A little lower down the value scale will be the frames made by companies such as Newcomb-Macklin and Thanhardt-Burger. These are typically hand-carved and hand-gilded and can bring prices in the low thousands if a particularly nice frame. While these companies did make Louis-style frames, they are generally more associated with impressionist and craftsman-style frames. These frames, (and others like them by similar makers) you might very well find. Look either for labels on the back or hand-written frame maker's notes. These latter will usually reference size, color of base coat, and type of leaf used (22 gold leaf vs. metal leaf). Don't let the quality of the artwork deter you... more than once I have found exceptional frames with really bad paintings in them ;-) Another frame company to watch for is House of Hedenryk. These frames often are Louis-style and will frequently have a pale wash. These frames were typically used for works by 20th century school of Paris artists, many of whom were carried by galleries in the US. Look for the Heydenryk label on the back of the frame, which ideally will still be in place. Thrift stores and resale stores are good hunting grounds for these frames since many people mistake them for later "shabby chic" frames. I have purchased Heydenryk frames for as little as $10 at re-sale stores and had them bring over $100 on eBay. Especially nice ones can bring several hundred dollars, so keep your eyes peeled! The New Deal enacted during the Depression included an agency known as the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This agency encompassed a number of areas, with the largest focus being on road, bridge, and dam construction. It employed millions of jobless Americans and much of their work, including the TVA, became fixtures in American infrastructure.

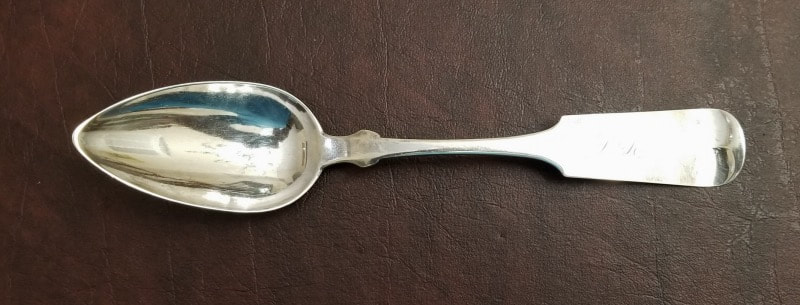

Interestingly, the WPA also included funding for artists. To its credit, no preference was given to "sellable" art and thus even abstract painters like Jackson Pollock were given support. That said, the term "WPA art" tends to connote artwork that often depicted construction scenes and social realism, often in mural form. It is also often associated with the Regionalism movement epitomized by artists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Today, this art remains popular among collectors. As one might suspect, the highest prices are commanded by the biggest art names. Still, even strong works by lesser known painters can bring good sums in the art market and should be something for a collector to consider acquiring. One note of caution: true WPA works (i.e. those directly paid for by the government) were ruled by the courts some time back to still be the property of the US government. Many of these works, originally display in state and county buildings throughout the US, were dispersed over the years and fell into private hands. Should you come by one of these works (often times they will have a WPA plaque on the frame), tread carefully if you go to sell it. If it comes to the government's attention, they will confiscate the work. Usually you will be given the opportunity to donate it and receive a tax deduction... otherwise, it will simply be taken away from you. My advice: make the donation ;-) With formal entertaining almost a bygone tradition and precious metals at strong levels, it is no wonder that many people have cashed in their sterling silver flatware for money. And while it is true that gold brings far more than silver, if you have enough of the latter it can still add up to a nice payday. So, if you decide to go looking through your drawers for goodies to monetize, just remember that because a piece does not say "sterling", it doesn't mean that your item is worthless silver plate. Listed below are some things to look for.

First, the easy one: the number 925. Sterling silver, like gold, is often represented by a purity number. And as many - if not most- of us know, sterling silver's purity number is 925. Often times the "925" can be very tiny or worn almost smooth but if you see it, you have sterling. Another number you might see is 800, which I have also heard referred to as "Russian silver". Many people think that the 800 is a dealbreaker but nothing could be further from the truth. The 800 simply means that the item is 800 parts silver vs. 925. It isn't sterling but you will still get close to the sterling price from a reputable metals buyer. Lastly, you might also see pieces (and these will usually be 19th century or earlier) that are "coin silver". This is the term used for American pieces made prior to the introduction of the assay system in the late 19th century and as the name implies, the silver was the same purity as that of minted coins. As a general rule of thumb, coin silver will be about 900 parts silver so it is almost the same as sterling. Sometimes these pieces will be marked "coin" or "pure coin" but often times, they are unmarked. Instead, look for the distinctive fiddle shape of the handles and also maker's marks. Most coin silver pieces will bear the maker's cartouche and frequently, pseudo-hallmarks as well. These hallmarks often are meaningless since there was no assay system at the time and instead were added to make the pieces look like their more desirable English cousins. Now, the warning flags: If you see the terms "German Silver", "Alpaca", or "Alpaca Silver" that means they are not silver at all. Instead, they are alloys that looks like silver but have no precious metal value at all. The letters "EPNS" means another dud... this stands for "electro plate nickel silver" and is just that... silver plate. Lastly, if you can find no marks, then always take it along with your other pieces to whomever you plan to sell to. Some of the Scandinavian silver, for example, is sterling but unmarked so better safe than sorry. A reputable metals buyer will be able to test it in the spot and give you the good or bad news. Hopefully, the news will be good ;-) The early 19th century saw the dawn of a great era of discovery in the natural sciences. Darwin, Lyell, and others advanced radically new theories that laid the foundations for modern biology, geology, and other fields. In France, one of the most prominent figures in this arena was Baron Georges Cuvier (1769-1832). Born Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric but known as "Georges" Cuvier, he is recognized today as one of the founders of modern paleontology. He was so prominent, in fact, that he is one of only 72 people whose name is inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

In 1817, he undertook perhaps his most ambitious project, which was a four volume work entitled "The Animal Kingdom". In this work, he endeavored to catalog as many living species as possible and had meticulous engravings prepared for each described animal. The work was later reprinted several times but the best known of these reprintings is the 1834 edition published in London by G. Henderson. Since color printing had not yet been introduced, the engravings were often hand-colored and may still be acquired at very nominal sums today. Speaking both as an appraiser and former fine art dealer, my own opinion is that these hand-colored engravings are still bargains if you are looking for decorative pieces with good history behind them. Look for examples from the 1834 reprinting with crisp color and minimal age-toning of the paper. Also, consider being selective in your subject matter. My own favorites are the exotic fish and birds... not so much the snakes and insects ;-) Nicely framed, these engravings are wonderful for powder rooms and small in-fill spaces where a painting might not be a good fit. When the subject of natural history comes around, it often conjures in people's minds images of boring college lectures and nerdy "rockhounds" with agate bolo ties. And, having gotten two geology degrees earlier in life, I can attest that those images are not always inaccurate ;-) But make no mistake: there is a thriving market for important geological specimens... think "trophy fossils"... among deep-pocketed collectors.

Chief among the most sought-after specimens are dinosaur skeletons, especially predators like T rex. These skeletons can bring millions of dollars at auction, which is plenty of incentive to loot from public lands or bring in specimens illegally from other countries. China and Mongolia in particular have yielded some amazing specimens but also have essentially banned the export of significant vertebrate fossils. More than one dealer in the US has been caught trying to sell smuggled specimens and gone to jail for their troubles. Another problem with the market for high-dollar fossils is the incentive to fake items. Morocco has been a hotbed for years of fake fossils, even down to the level of specimens that would normally sell in the low hundreds. China is another major source of fakes, especially small vertebrate fossils and trilobites. Speaking as a long-time fossil collector, I will share that I generally will not buy anything that has either country as a point of origin. That is not to say that some of the specimens aren't legitimate... instead, for me, the risk of buying a fake just outweighs the possibility of getting something good. Even if you aren't a collector per se, fossils and minerals can still serve as eye-catching objets d'art or decorative accessories. Should you decide to add one or more to your decor, here are a few tips to consider: First, as with a nice antique or piece of art, always try to deal with a reputable seller who can give you the relevant information about a piece, including any repair, restoration, or enhancement. By "enhancement" I refer to fossils being added to a plate (often referred to as "dropped in"), stained or painted in, or in some cases (hellooo Morocco) completely made up. Second, avoid specimens from "problem" sources like Morocco and China (see my previous comment). Third, research before you buy to make sure you are not wildly overpaying. Some items such as Megalodon shark teeth, have significant nuances in pricing relative to size. A 3" tooth may sell for $60 but a 6" tooth will usually sell for at least $400. With shark teeth in particular, size matters! In closing, here is a link to a fascinating video that recently appeared on the Wall Street Journal's web site. An excellent look into the public-private debate and one that will give you an idea of some of the values being assigned to trophy fossils these day. https://www.wsj.com/video/science-and-commerce-clash-over-selling-dinosaur-fossils-for-profit/91A24839-3332-4C0A-B019-848BE2472F50.html?mod=searchresults&page=1&pos=2 Few businesses will likely emerge unchanged in any way once we are past the current pandemic. Ironically, my appraisal business may one of them, but not so for the broader antiques and fine art fields. Here are some of the trends and aftermaths I suspect we will see.

First, it is likely that at least some of the galleries and antiques stores simply will not return. The galleries are in an especially challenging environment since much of the selling typically happens at crowded openings or when the gallery staff can closely interact with one or more customers. This will not be the norm for a while and whether a gallery can survive the ensuing sales drought will depend on several factors, including overhead and the ability to increase successful online strategies. Antiques stores may fare better although that industry has been struggling for some time due in large measure to the steady erosion of interest in the merchandise among younger demographic cohorts. Again, moving to a stronger online presence or perhaps going completely virtual will likely be a necessary path for survival in many cases. I have actually been seeing this for some time on the Etsy platform, where it is clear antiques vendors have joined in sizable numbers. Speaking of Etsy, it has been interesting to watch how Etsy has quickly evolved from being a site for handmade crafts to encompassing an enormous variety of goods, including fossils and minerals, antiques, fine art, and pretty much anything that might be reasonably included in the handmade/vintage categories. For the record, I have a store there myself (MadCatEmporium) where I market my own local finds and have found the platform to be a delight to use. Another industry that is absolutely being altered by the pandemic is the auction business. In-person previews are largely out now and it is hard to say when they might some day be revived. Again, it is the online strategy that is now being maximized and which will likely benefit most those auction houses with the capital to stand out in already crowed arena. The downside to this trend though is that the major houses are presently shedding staff and ordering significant pay cuts for those that remain employed. Look for leaner staffing with an emphasis on good photography and condition reports. For those of us who have fond memories of hunting nice pieces at antiques stores or mingling at art openings, the changes being wrought will make us ever more wistful. But, these changes have also long been in the making. To my mind, the current pandemic is simply imposing an unwelcome Darwinism on those business who were already struggling most and also forcing survival changes at an accelerated pace. One thing for sure though is that the retail and auction landscape will be quite different when the pandemic has passed. By virtue of age, almost any antique object will have a story behind it. Some will be interesting or important, most mundane. Some objects will never have their history or story revealed, others will rely on notes or oral history handed down from prior generations. In a few cases, however, the object itself will have all the information you need front and center.

Such was the case with an antique bottle that I recently found at a local re-sale store. Bottles are not a specialty of mine but the obvious age and the SC (for South Carolina), combined with the reasonable price, was all the incentive I needed to become the new owner. Speaking as an appraiser, I'll share with you that Southern items almost always command a premium in the marketplace for historical items. A little quick research led to an interesting story behind the bottle, which is as follows: In 1893, the then-governor of South Carolina, Ben Tillman (known as "Pitchfork Ben" due to his farming background), decided to create a state-run liquor monopoly called the South Carolina Dispensary. Located first in Edgefield, SC, the dispensary offered spirits in half-pint, pint, and half-quart bottles. The most common sort are the "Jo Jo flasks" such as the one pictured above. Soneware jugs, made both in SC and VA, were also used. Originally, most bottles were made by out-of-state glass companies but in 1902, Tillman moved the dispensary to Columbia where bottles were then made by the Carolina Glass Co. It was a short-lived enterprise, however, with the dispensary closing its doors in 1907. The Jo Jo flasks are easy to spot, with a large SCD monogram on the front of the flask and "S C Dispensary" embossed beneath it. The glass company will usually appear on the reverse side... in this case my bottle was marked "C G Co" for the Carolina Glass Company. Hence, it probably dates to 1902-1907. A second type of bottle was the "Union flask", which lacks the monogram but bears two titles, S C Dispensary and South Carolina Dispensary. The common clear bottles usually trade in the $75-150 range but rare forms can bring $20,000 or more. For a much more in-depth discussion of the dispensary and the types of bottles they used, you can follow this link to Wikipedia. Here is the link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Carolina_Dispensary. I found it to be a fascinating read and now know to be much more attentive when I run across old bottles. Whether I ever find one of the really rare SC Dispensary flasks is anyone's guess but the story behind the bottle I did find was a good one. With 2019 now behind us, early 2020 seems to be a good time to reflect on the state of today's markets for antiques, art, and collectibles. I don't feel that there were any momentous changes in 2019... just a continuation of past trends with perhaps a slight acceleration. Here are my thoughts:

Without a doubt, the fair market value for most things continued to trend lower in 2019. This was largely across the board in all categories, with traditional forms having an especially hard struggle. By traditional, I especially mean categories such as early furniture, china, sterling silver, etc. Or, as one client put rather humorously, "anything that would have been in my grandmother's house". More contemporary categories such as Mid-century Modern seem to retain some strength, although my sense is that the popularity if this particular category has waned somewhat as well since the end of the TV show "Mad Men". Pockets of strength can be found in areas such as fine wines, vintage automobiles, celebrity memorabilia, and other more esoteric categories. Early technology such as early Apple computers also can bring strong dollars for the right piece. As in the past, an exception will always be made for the very best examples of anything, even in struggling categories like early Americana. Similarly, blockbuster items will always have a strong appeal as well... an example would be the famous Mustang used in the movie Bullitt, which recently sold for $3 million. Looking ahead in 2020, I see little reason to think the above-mentioned trends will turn around in any meaningful way. My advice to clients continues to be that if you are thinking of de-accessioning items, do it ASAP while there is at least still some sort of market to sell into. Just be aware that auction houses are getting ever more finicky about their value thresholds, so don't expect them to take just anything. It amazes me to see how so many items that once would have sold in ones or twos are now being shoved into a single lot of 10 or more similar pieces. This in turn makes it harder to attract a lot of bidders, since most people aren't looking for 10 or 12 pieces of anything. So, to conclude, you don't need to fasten a seat belt for 2020 as far the resale markets go but instead expect a continued gentle descent in values. The one wildcard will be the 2020 presidential election. Depending on how that shakes out, a loss of confidence in the financial markets could make for a nasty downturn, which will only incite more people to sell and make for even fewer buyers. Something to think about... |

AuthorBryan H. Roberts is a professional appraiser in Sarasota, FL. He is a member of the Florida State Guardianship Association and currently serves on the board of the local FSGA chapter. He is a past president of the Sarasota County Aging Network, a non-profit that provides grants to other non-profits benefiting seniors in need and is also a board member of PEL, an area non-profit whose resale store profits support programs and scholarships for at-risk and disadvantaged youth. He is certified in the latest Uniform Standards of Appraisal Practice (USPAP) Equivalent Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed